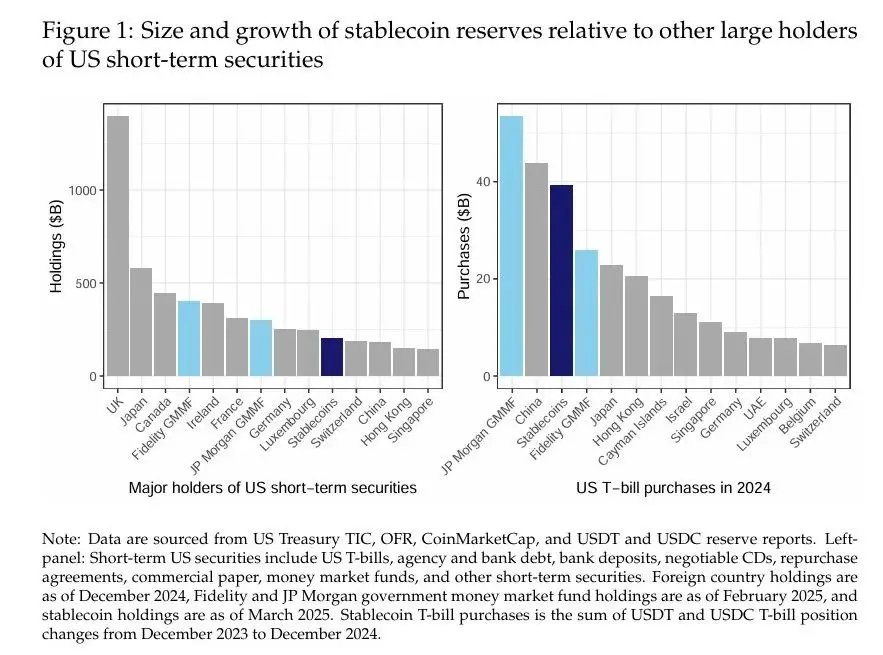

Dollar-backed stablecoins have experienced significant growth and are poised to reshape financial markets. As of March 2025, the total assets under management of these cryptocurrencies, which are pegged to the dollar at face value and backed by dollar-denominated assets, exceeded $200 billion, surpassing the short-term US securities held by major foreign investors such as China (Figure 1, left). Stablecoin issuers, particularly Tether (USDT) and Circle (USDC), primarily back their tokens with U.S. short-term Treasury bills (T-bills) and money market instruments, making them significant participants in the short-term debt market. In fact, in 2024, dollar-backed stablecoins purchased nearly $40 billion in U.S. short-term Treasury bills, a scale comparable to that of the largest U.S. government money market funds and exceeding the purchase volumes of most foreign investors (Figure 1, right panel). While previous research has primarily focused on the role of stablecoins in cryptocurrency volatility (Griffin and Shams, 2020), their impact on the commercial paper market (Barthelemy et al., 2023), or their systemic risks (Bullmann et al., 2019), their interactions with traditional safe-haven asset markets remain under-explored.

This paper investigates whether stablecoin flows exert measurable demand pressure on U.S. Treasury yields. We document two key findings. First, stablecoin flows depress short-term Treasury yields, with an impact comparable to that of small-scale quantitative easing on long-term yields. In our most stringent specification, we overcome endogeneity issues by using a series of crypto shocks that affect stablecoin flows but do not directly impact Treasury yields. We find that a $3.5 billion five-day stablecoin inflow (i.e., two standard deviations) reduces three-month Treasury yields by approximately 2–2.5 basis points (bps) over a 10-day period. Second, we decompose the yield impact into issuer-specific contributions, finding that USDT contributes the most to the suppression of Treasury yields, followed by USDC. We discuss the policy implications of these findings for monetary policy transmission, stablecoin reserve transparency, and financial stability.

Our empirical analysis is based on daily data from January 2021 to March 2025. To construct a measure of stablecoin flows, we collected market capitalization data for the six largest USD-backed stablecoins and aggregated them into a single figure. We then used the 5-day change in total stablecoin market capitalization as a proxy for stablecoin inflows. We collected data on the US Treasury yield curve and cryptocurrency prices (Bitcoin and Ethereum). We selected the 3-month Treasury yield as our outcome variable of interest because the largest stablecoins have disclosed or publicly stated this maturity as their preferred investment horizon.

A simple univariate local projection linking changes in the 3-month Treasury yield to 5-day stablecoin flows may be subject to severe endogeneity bias. In fact, this “naive” specification suggests that a $3.5 billion inflow of stablecoins is associated with a decline of up to 25 basis points in the 3-month Treasury yield over 30 days. This magnitude of effect is astonishingly large, as it implies that a 2-standard-deviation inflow of stablecoins has an impact on short-term interest rates comparable to a cut in the Federal Reserve’s policy rate. We believe these large estimates can be explained by the presence of endogeneity, which biases the estimates downward (i.e., larger negative estimates relative to the true effect) due to omitted variable bias (because potential confounding factors are not controlled) and simultaneity bias (because Treasury yields may influence stablecoin flows).

To address endogeneity issues, we first extend the local projection specification to control for changes in the US Treasury yield curve and cryptocurrency prices. These control variables are divided into two groups. The first group includes forward changes in U.S. Treasury yields for all maturities except the 3-month term (from t to t+h). We control for the evolution of the forward Treasury yield curve to isolate the conditional effect of stablecoin flows on the 3-month yield, given changes in neighboring term yields, within the same local projection horizon. The second group of control variables includes 5-day changes (from t-5 to t) in Treasury yields and cryptocurrency prices to control for various financial and macroeconomic conditions potentially associated with stablecoin flows. After introducing these control variables, the local projection estimates that a $3.5 billion stablecoin inflow reduces Treasury yields by 2.5 to 5 basis points. These estimates are statistically significant but nearly an order of magnitude smaller than the “naive” estimates. The decay in the estimates is consistent with our expectations regarding the sign of endogeneity bias.

In the third specification, we further strengthen identification through an instrumental variables (IV) strategy. Following the method of Aldasoro et al. (2025), we instrumentalize the 5-day stablecoin flow using a series of crypto shocks, which are constructed based on the unpredictable components of the Bloomberg Galaxy Crypto Index. We use the cumulative sum of the crypto shock sequence as the instrumental variable to capture the unique yet persistent nature of crypto market booms and busts. The first-stage regression of 5-day stablecoin flows on cumulative crypto shocks satisfies the correlation condition and shows that stablecoins tend to experience significant inflows during crypto market booms. We believe the exclusion restriction is satisfied because the specific crypto boom is sufficiently isolated to not have a meaningful impact on Treasury market pricing—unless through inflows into stablecoins, issuers use these funds to purchase Treasuries.

Our IV estimates suggest that a $3.5 billion inflow of stablecoin liquidity would reduce the 3-month Treasury yield by 2–2.5 basis points. These results are robust to changing the set of control variables by focusing on maturities with lower correlation to the 3-month yield—if anything, the results are slightly stronger in magnitude. In additional analysis, we did not find spillover effects from stablecoin purchases on longer maturities such as 2-year and 5-year, though we did find limited spillover effects at the 10-year maturity. In principle, the effects of inflows and outflows may be asymmetric, as the former allows issuers some discretion in timing purchases, whereas such flexibility does not exist under tight market conditions. When we allow estimates to differ under inflow and outflow conditions, we do find that outflows have a quantitatively larger impact on yields than inflows (+6-8 basis points vs. -3 basis points). Finally, based on our IV strategy and baseline specifications, we also decomposed the estimated yield impact of stablecoin flows into issuer-specific contributions. We found that USDT flows had the largest average contribution, at approximately 70%, while USDC flows contributed approximately 19% to the estimated yield impact. Other stablecoin issuers contributed the remainder (approximately 11%). These contributions were qualitatively proportional to issuer size.

Our findings have important policy implications, especially if the stablecoin market continues to grow. Regarding monetary policy, our yield impact estimates suggest that if the stablecoin industry continues to grow rapidly, it could eventually affect the transmission of monetary policy to Treasury yields. The growing influence of stablecoins in the Treasury market could also lead to a scarcity of safe assets for non-bank financial institutions, potentially affecting liquidity premiums. Regarding stablecoin regulation, our results highlight the importance of transparent reserve disclosure to effectively monitor concentrated stablecoin reserve portfolios.

When stablecoins become large investors in the Treasury market, they may generate potential financial stability implications. On the one hand, they expose the market to the risk of potential sell-offs if major stablecoins face a run. In fact, our estimates suggest that this asymmetric effect is already measurable. Our estimated magnitude may represent a lower bound on the potential sell-off effect, as they are based on a sample primarily from growth markets and may underestimate the potential for nonlinear effects under severe stress. Additionally, stablecoins themselves may facilitate arbitrage strategies, such as Treasury basis trading, through investments like Treasury-backed reverse repurchase agreements, which are a key concern for regulators. Equity and liquidity buffers may mitigate some of these financial stability risks.

Data and Methodology

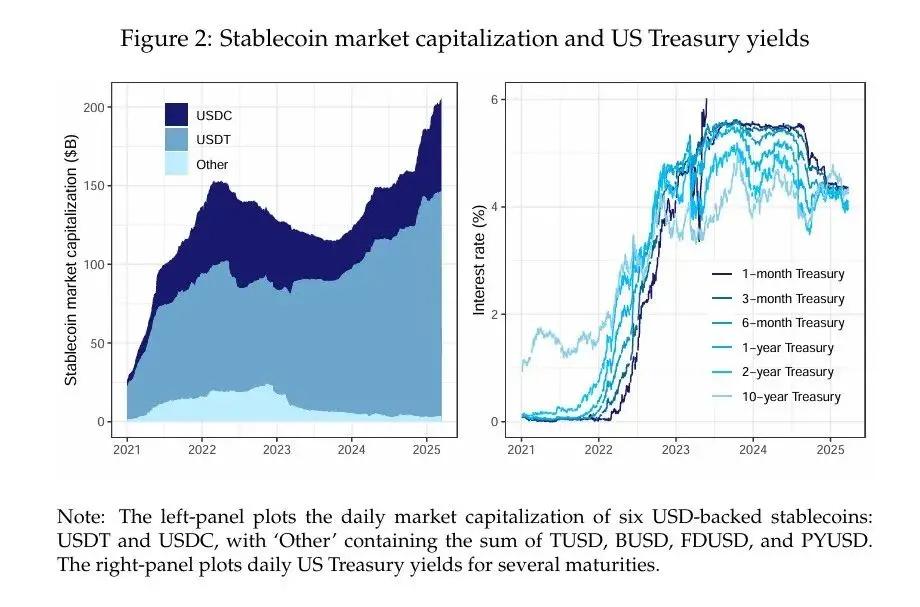

Our analysis is based on daily data from January 2021 to March 2025. First, we collected market capitalization data for six USD-backed stablecoins from CoinMarketCap: USDT, USDC, TUSD, BUSD, FDUSD, and PYUSD. We aggregated the data for these stablecoins to create a metric measuring the total market capitalization of stablecoins, then calculated its 5-day change. We obtained daily prices for Bitcoin and Ethereum, the two largest cryptocurrencies, from Yahoo Finance. We retrieved daily series of the US Treasury yield curve from FRED. We considered the following maturities: 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 10 years.

As part of our identification strategy, we also used the daily version of the crypto shock series proposed by Aldasoro et al. (2025). Cryptocurrency shocks are calculated as the unpredictable component of the Bloomberg Galaxy Crypto Index (BGCI), which captures broad cryptocurrency market dynamics (we will provide more details on cryptocurrency shocks below).

Figure 2 shows the market capitalization of USD-backed stablecoins and U.S. Treasury yields during the sample period. Stablecoin market capitalization has been rising since the second half of 2023, with significant growth at the beginning and end of 2024. The industry is highly concentrated. The two largest stablecoins (USDT and USDC) account for over 95% of the outstanding amount. The Treasury yields in our sample encompass both the rate-hiking cycle and the subsequent pause and easing cycle that began around mid-2024. The sample period also includes a distinct period of yield curve inversion, most notably the deep blue line moving from the bottom to the top of the yield curve.

Conclusions and Implications

Scale. It is estimated that a yield impact of 2 to 2.5 basis points stems from a $35 billion (or 2 standard deviation) inflow of stablecoins, with the industry’s size estimated to be approximately $200 billion by the end of 2024. As the stablecoin industry continues to grow, it is not unreasonable to expect its footprint in the Treasury market to increase as well. Assuming the stablecoin industry grows tenfold to $2 trillion by 2028, the difference in five-day flows would increase proportionally. Then, the 2-standard deviation flow would reach approximately $11 billion, with an estimated impact on Treasury bill yields of -6.28 to 7.85 basis points. These estimates suggest that the growing stablecoin industry could eventually suppress short-term yields, thereby fully affecting the transmission of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy to market yields.

Mechanism. Stablecoins have at least three channels through which they can influence pricing in the Treasury market. The first is through direct demand, as stablecoin purchases reduce the available supply of fiat currency, provided that funds flowing into stablecoins do not flow into Treasury bills. The second channel is indirect, as stablecoin demand for U.S. Treasuries may alleviate dealers’ balance sheet constraints. This, in turn, affects asset prices, as it reduces the amount of Treasury supply dealers need to absorb. The third channel is through a signaling effect, as large inflows may signal institutional risk appetite or lack thereof, which investors then factor into the market.

Policy implications. Policies surrounding reserve transparency will interact with stablecoins’ growing footprint in the Treasury market. For example, USDC’s granular reserve disclosure enhances market predictability, while USDT’s opacity complicates analysis. Regulatory requirements for standardized reporting could mitigate systemic risks from concentrated Treasury ownership by making some of this liquidity more transparent and predictable. Although the stablecoin market remains relatively small, stablecoin issuers are already a meaningful participant in the Treasury market, and our findings suggest that yields have already been impacted at this early stage.

Monetary policy will also interact with stablecoins’ role as investors in the Treasury market. For example, in scenarios where stablecoins become very large, stablecoin-driven yield compression could weaken the Federal Reserve’s control over short-term interest rates, potentially requiring coordination among regulators to effectively influence financial conditions. This view is not merely theoretical—for instance, the “green dilemma” of the early 21st century stemmed from the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy failing to impact long-term Treasury yields as expected. At the time, this was primarily due to the significant demand from foreign investors for U.S. Treasury bonds, which influenced pricing in the U.S. Treasury bond market.

Finally, the emergence of stablecoins as investors in the Treasury bond market has clear implications for financial stability. As discussed in the literature on stablecoins, they can still operate, with their balance sheets exposed to liquidity and interest rate risks, as well as some credit risks. Therefore, if a major stablecoin faces severe redemption pressure, especially given the lack of access to a discount window or a lender of last resort, concentrated positions in Treasury bills could lead to market sell-offs, particularly for those that are not immediately maturing. The evidence we provide on asymmetric effects suggests that the impact of stablecoins on the Treasury market may be greater in environments characterized by large-scale and abrupt outflows. In this regard, the magnitude suggested by our estimates may represent a lower bound, as they are based on a sample primarily comprising a growing market. As the stablecoin industry expands, this situation may evolve, potentially exacerbating concerns about the stability of the Treasury market.

Limitations. Our analysis provides some preliminary evidence of stablecoins’ emerging footprint in the Treasury market. However, our results should be interpreted with caution. First, we face data constraints in our analysis due to incomplete disclosure of the maturity dates of USDT reserve portfolios, leading to identification complexity. Therefore, we must assume which Treasury bill maturities are most likely to be affected by stablecoin flows. Second, we control for financial market volatility by including returns on Bitcoin and Ethereum as well as changes in yields across various Treasury bill maturities. However, these variables may not fully capture the risk sentiment and macroeconomic conditions that jointly influence stablecoin flows and Treasury bond yields. We attempted to address this issue through an instrumental variables strategy, but we acknowledge that our instrumental variables themselves may be subject to limitations, including specification errors in our local project model. Additionally, due to data constraints and the highly concentrated nature of the stablecoin industry, our estimates rely almost entirely on time-series changes, as the cross-sectional data is too limited to be utilized in any meaningful way.

In summary, stablecoins have become significant participants in the Treasury market, exerting a measurable and substantial influence on short-term yields. Their growth has blurred the lines between cryptocurrencies and traditional finance, prompting regulators to scrutinize reserve practices, potential impacts on monetary policy transmission, and financial stability risks. Future research could explore cross-border spillover effects and interactions with money market funds, particularly during liquidity crises.